When Councilmember Amanda Sandoval's father worked on statewide redistricting, she remembers him doing it the old-fashioned way. He would pull out a state map, setting it on a table in the family's restaurant, La Casita, where Sandoval worked as a waitress.

Her father, the late Paul Sandoval, was instrumental in shaping Colorado's statehouse districts during his career as a state lawmaker. Now, Sandoval is getting the chance to do the same kind of work, but instead of looking at the Front Range and San Luis Valley, she's focusing on Green Valley Ranch and Westwood.

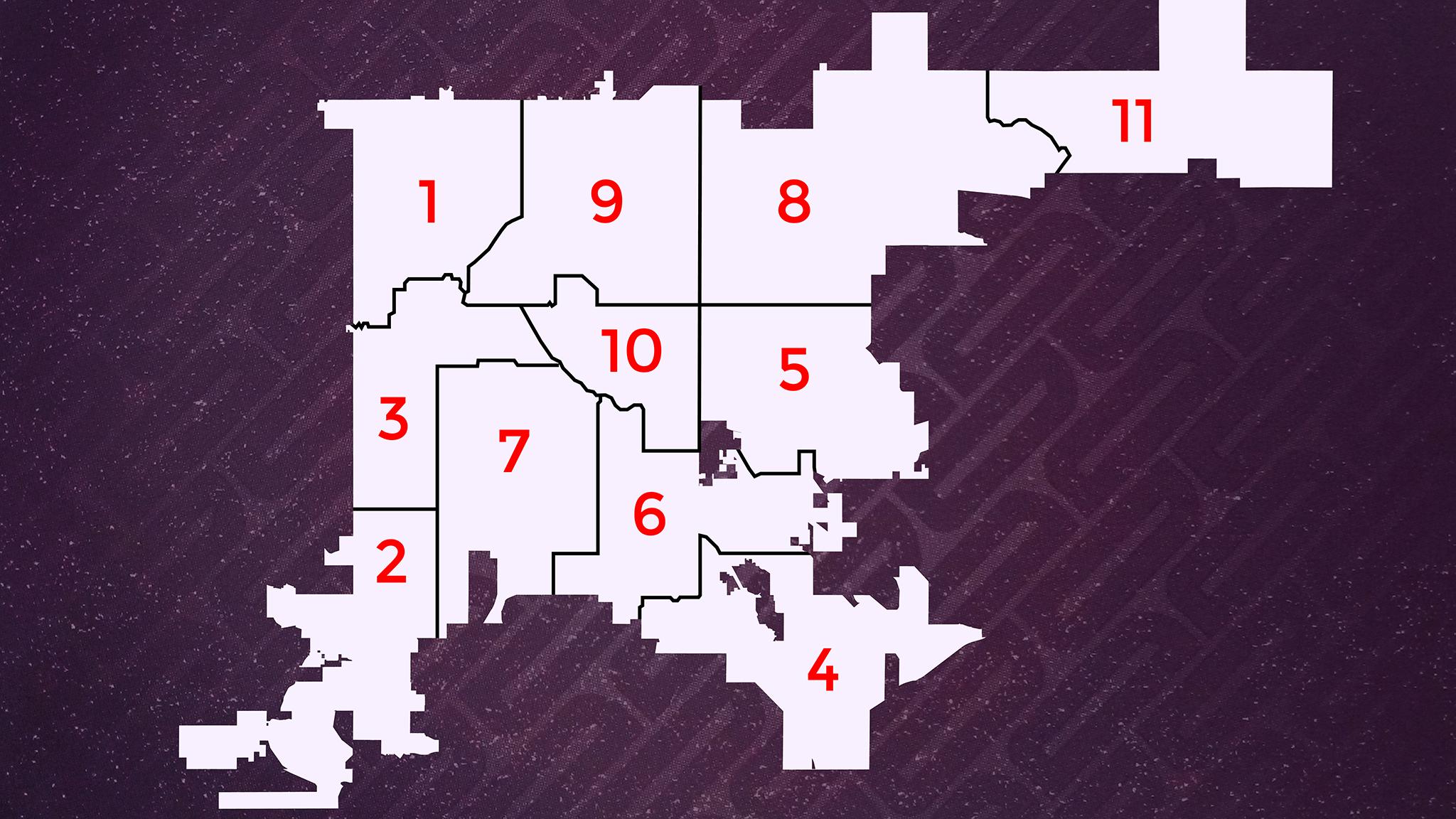

She's in charge of the effort to remap the city's 11 council districts, which cut Denver up into chunks. Each chunk has one council member representing it. Sandoval, for example, represents District 1, which sits in northwest Denver and includes neighborhoods like Berkeley and Sunnyside.

Sandoval, who requested to lead this process, readily admits most people probably don't know what council district they live in. So how can she convince people to care about redrawing a map most people have never seen before, or are familiar with at all?

"You hear that all the time about people, you hear public comments on Monday nights, that people want more of a voice," Sandoval said as she worked in her district offices on Platte Street recently. "And so here's a process where your voice is super important and you can shape Denver's history by representation."

She's hoping for more public interest as the city does something it's never done before: giving people the ability to draw their own maps.

Sandoval is working on a tight deadline since the new maps must be finalized by March.

The current timeline includes giving the public a chance to draw maps using a software called Maptitude starting next month. A public Maptitude training session will be held on Jan. 6 over Zoom. Weekly public meetings in different parts of the city would then take place in February to discuss the proposed maps and boundaries. Sandoval said the meetings will likely take place at local high schools.

"We want the public to be able to play with these same tools that council is working with to promote transparency in this process," said Emily Lapel, a legislative policy analysts that, like Sandoval, asked to work on this process. "It's a really cool tool."

City Council would consider and discuss the proposed maps in March, before voting on a final map the same month. It's a map that will determine what the districts look like for the next ten years, when some of Sandoval's current colleagues will no longer be on council, and new faces will emerge to take their place.

"It is really for this next generation that these maps really really matter," Sandoval said.

Setting that map by March is essential, since Denver voters decided to move municipal elections back a month. The 2023 municipal election will take place in April, and people who want to run for council districts need to know as soon as possible where they can run, which will be based on the new map.

"You have to live within your council district for a year to run," Sandoval said. "That's why we are on the timeframe we are on, is because of that mandate that we have."

Each council district is supposed to have only a certain number of people. The sweet number is about 65,047 people per the 11 districts in Denver, according to Lapel. She has a simple reason for why you should pay attention to local redistricting.

"It shapes the political landscape for a decade," Lapel said.

Because Denver grew by nearly 20 percent in the last 10 years, some current district's boundaries will need to shrink to accommodate the growth, while others may need to expand a bit. This is what the redistricting process will ultimately determine.

The city needs to pay close attention to how it's cutting up certain areas.

One way it does this is by looking at what's called "communities of interest."

These are geographical areas sharing cultural, historical or economic interests. One example would be in West Denver, which has a high concentration of Latino residents, with concerns ranging from potential displacement to traffic and public transit.

The public was able to use a software called Representable to identify communities of interest by drawing boundaries and answering questions about those communities. fourteen were identified, according to city staff.

Rebecca Theobald, an assistant research professor in the of geography department at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, has been advising the city's redistricting process.

Considering communities of interest is important because redistricting can determine who gets to represent an area. Theobald pointed out that dividing West Denver could lessen the likelihood of a Latino representing that area, which could be problematic.

Before the local redistricting process could start, other dominoes had to fall first.

To start, the U.S. Census data needed to be released. Using that data, the congressional map had to be redrawn, then the statehouse map had to be redrawn, and finally, Sandoval had to wait for Clerk & Recorder Paul López to set new precinct boundaries for the city.

López completed "reprecincting" earlier this month -- a bit ahead of schedule, since January had been the target date.

"We have an early Christmas present for you all," López told lawmakers when he unveiled the new map.

Precincts are the building blocks for council districts, since each one represents a certain number of voters, and, like council districts, are specific to certain areas of the city. They help determine what offices and issues people living in those precincts get to vote on. The city has 301 precincts, each one with about 1,500 voters, with a maximum of 2,000.

Precinct boundaries cannot be split; they have to stay intact. That's how they help create boundaries for each council district. So think of it like a square cut into four pieces; each of the four pieces represents a precinct. To create a council district, you could use any combination of the pieces, so maybe the top two, or the top two and one of the bottom pieces, or all four pieces. But you cannot split those pieces in half or in any other shape. They have to stay intact.

What do the council districts look like right now?

If you, dear reader, know what council district you live in, that's fantastic! If not, that's OK, too. The map boundaries aren't necessarily common knowledge. Here's what the map looks like now:

And here's a quick overview of what the districts currently look like: