On a Sunday afternoon in early October, Greg Caicedo was out for a bike ride. He was riding a route he has taken dozens of times along the Cherry Creek Trail. But this time, as he rode down the trail toward Wewatta Street, a group of four people on electric scooters came down a ramp and entered the trail, moving fast without pausing to yield.

Caicedo remembers colliding with the scooters and hitting the ground hard. The scooter riders fled the scene while a passerby called for an ambulance. Caicedo ended up in the emergency room at Denver Health with a broken clavicle, five broken ribs, a collapsed lung, serious bruising down his leg and a concussion.

He spent three nights in the hospital and took a week off work. Even with insurance, Caicedo says he has spent thousands of dollars on doctors appointments and physical therapy.

The most dangerous vehicles on Denver's roads are cars. In 2022, Colorado saw the greatest number of traffic fatalities since 1981, including a record number of pedestrians and motorcyclists, while traffic fatalities continue to rise nationwide. Like pedestrians and cyclists, scooter riders are often victims of car drivers.

But as electric scooter ridership grows in Denver, cyclists and pedestrians are exposed to another risk: reckless scooter riders moving fast on bike lanes and trails originally designed for biking and walking.

In the weeks since his collision, Caicedo has tried to find justice for the hit-and-run. But because electric scooters exist in an in-between space, not classified as a motor vehicle but often with the potential for more serious injuries than a regular bike, answers have been hard to find.

"I think the thing that's probably most disturbing is the fact that they hit me and then left the scene without trying to render aid or call emergency services or anything," he said. "I don't think there is any recourse."

Caicedo believes that Lime has the information of the people who likely hit him, but he cannot access that information.

Caicedo's Apple watch pinged his girlfriend, Colleen Tully, the moment he hit the ground, and the GPS workout app Strava was tracking his ride. That means he can pinpoint a pretty specific location and time for the incident. Tully reached out to Lime's law enforcement team, which said it was able to identify trips in the area at that day and time.

But Lime will not release that information to just anyone. Debates over data privacy have played out within tech companies for years, with concerns over misuse by private citizens, companies, law enforcement or governments.

Lime's privacy policy prevents the company from releasing rider information to private citizens, but Lime said it would release that information to police.

"We are investigating this incident internally and stand ready to assist law enforcement in their investigation as well," said Lime spokesperson Jacob Tugendrajch.

But a spokesperson for the Denver Police Department (DPD) said it cannot legally request that information without more evidence.

"Investigating a hit and run [crash] involving E-scooters and pedestrians provide many challenges for investigators. Identifying the scooter that was used in the incident is one of those challenges," said a spokesperson for DPD. "A certain amount of proof is needed to be able to obtain a search warrant to obtain the information of the person that rented the scooter. Generally, a serial number of the involved scooter that was used is needed for a search warrant to be signed by a judge."

Even with rider information, DPD said it would need more evidence like a witness or surveillance footage. Police said they are still investigating the collision and declined to provide any documents related to the case. Denverite reviewed emails with Lime, paperwork from DPD and a paramedic's report provided by Caicedo related to the crash.

Denver defense attorney Matthew Hand said trails leading to a dead end happen a lot with hit-and-runs involving cars as well. For example, police might be able to track down a license plate number, but that does not guarantee that the car owner was driving the vehicle at the time of the accident.

"A big part of what's at play is just that this is non-traditional," he said.

Even if Caicedo could find out who hit him, his legal options are limited.

Companies like Lime require riders to sign user agreements assuming all risks for the scooter and all liability for any injuries.

"The way that the system is set up, Lime is bulletproof, the product owner does not hold any accountability for the misuse of their product," Caicedo said. "All of it is on the individual users, and then the individual users that actually use the actual product are difficult to find."

Meanwhile, unlike with car insurance, scooter riders are typically not insured for accidents they might cause. That means financial recourse would be difficult even if Caicedo knew who was responsible. Instead of two insurance companies fighting over who has financial responsibility, recourse might require a criminal investigation. If a scooter rider was found responsible, they could have to pay thousands of dollars without the protection of something like car insurance.

Caicedo said DPD told him they would not pursue a criminal investigation. When asked by Denverite, DPD said that "officers consider all possible options when undergoing an investigation" and that Caicedo's case is still open.

While justice is often elusive, injuries involving electric scooters are on the rise.

Electric scooter companies, including Lime, first arrived in Denver in 2018. At first the city issued permits to seven different companies before awarding control to just Lime and Lyft in 2021. Scooter companies and city officials touted the scooters as a micro-mobility program, decreasing car use and connecting people to public transportation in a city where many people live far from their nearest train or bus stop.

The scooters have been popular. According to Lime spokesperson Tugendrajch, Denverites have taken more than 10 million trips on Lime scooters in Denver. He said that incident rates globally have gone down over time, and that an increase in injuries could be due to more people overall riding scooters and the use of private scooters with less regulation.

"While we are proud that 99.99% of our rides globally are completed without incident, we never stop trying to improve on safety, including by preventing future incidents and cracking down on irresponsible riders," Tugendrajch said.

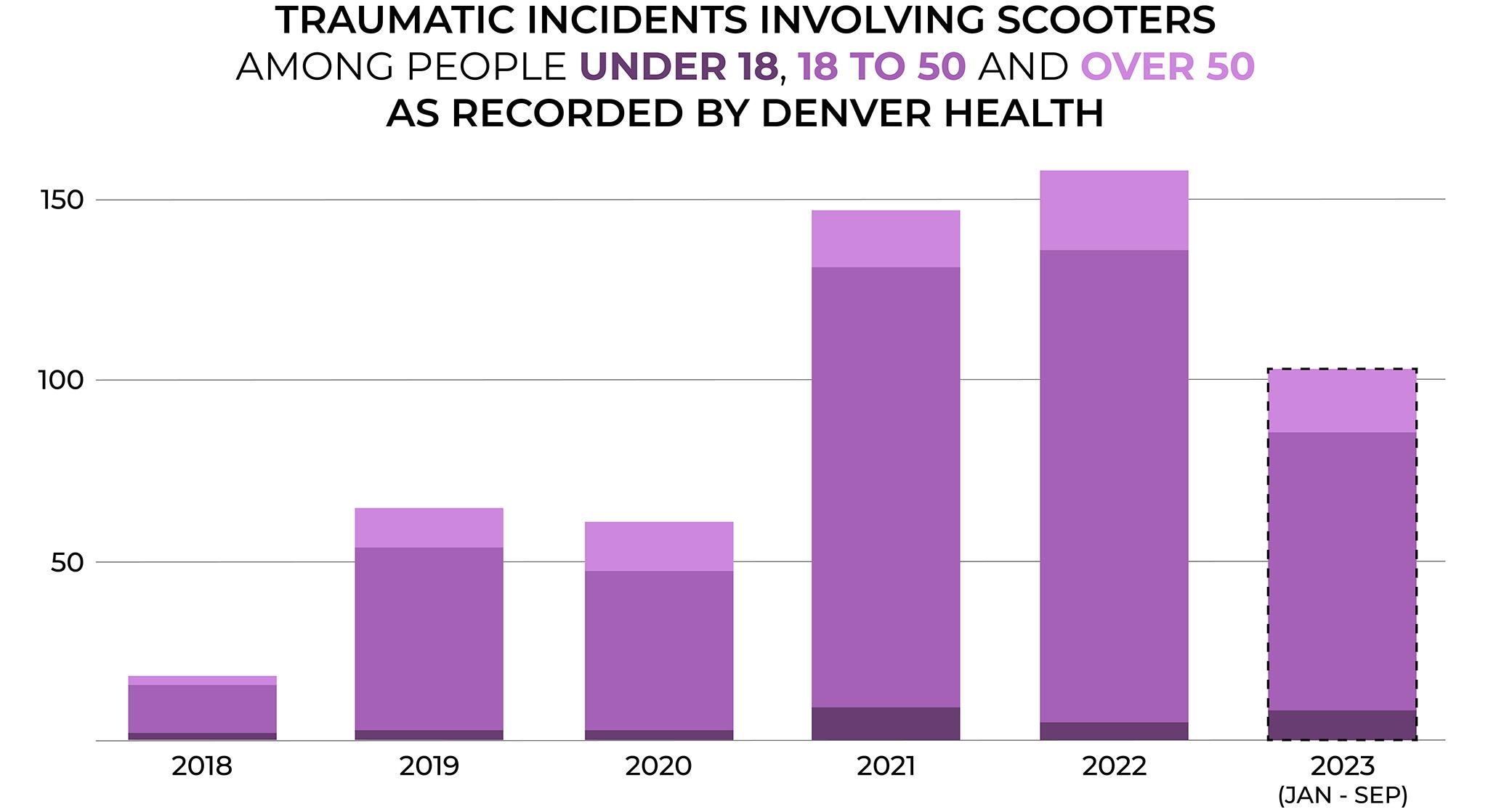

In Denver, the overall number of crashes involving electric scooters has increased along with ridership. According to data from Denver Health, the number of trauma patients involved in electric scooter crashes admitted to Denver Health rose from 18 people in 2018 to 158 people in 2022. That includes crashes involving cars, cyclists, pedestrians or just the scooter rider themselves. The actual number of scooter incidents is likely much higher; that figure does not include people who brought themselves to Denver Health with less severe injuries, or people admitted to other hospitals across the city.

A 2022 study of nearly 200 people involved in electric scooter crashes conducted by a group of orthopedists in Denver found that the average hospital visit cost $14,200.

Missy Anderson, a registered nurse and pediatric trauma program manager at Denver Health, tracks a wide range of trauma data at the hospital including bike and scooter incidents. While people driving cars at high speeds are responsible for more collisions and fatalities, Anderson said that people hit by electric scooters going at full speed, often on trails or sidewalks, tend to have worse injuries than pedestrians hit by cars at low speeds.

While Lime and Lyft scooter rentals in Denver max out at 15 miles per hour, privately purchased scooters can reach 30 miles per hour or more.

"These folks that are pedestrians and get hit by a scooter, these folks tend to have pretty serious injuries because they're just walking and then a scooter coming 30 miles an hour hits them," Anderson said. "They got bad head injuries sometimes, multiple broken bones."

In 2022, the city expanded its scooter safety efforts. But some experts and crash victims say it's not enough.

That summer, the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI) added stencils to the sidewalk in high ridership areas reminding scooter riders that they cannot ride on the sidewalk. Scooters are only allowed on sidewalks if they are part of bike lanes, and riders must go no more than 6 miles per hour and yield to pedestrians. The city also added stickers to some scooters instructing riders to avoid riding on sidewalks or parking scooters in the middle of the sidewalk.

The city also invested in technology that slows rented scooters down in high traffic areas, such as near Coors Field during baseball games. Denver officials also hosted in-person education events on scooter safety and launched a reporting tool where people can report scooters and e-bikes parked incorrectly or report riders violating rules.

"As Denver's Shared Bike and Scooter program grows in popularity, we're continuing to explore ways to keep all street users safe," said DOTI spokesperson Nancy Kuhn. "We're particularly focused on making infrastructure improvements to create a safe riding environment such as installing more protected lanes for people on bikes and scooters to share."

While bike lanes and trails can protect scooter riders from cars, they can also increase dangers for cyclists they share the road with like Caicedo.

Caicedo wants to see Denver do more to regulate electric scooters and companies take more responsibility for injuries. He suggested wider bike lanes to better accommodate scooters along with cyclists, and better signage or gates at the entrance to trails. The Cherry Creek Trail has a 15 mile per hour speed limit and people going above that are subject to tickets, but enforcement is inconsistent.

"I just wish that there'd be more consideration in a crowded city, where you've got lots of people in different states of physical capability and age and children and elderly," Caicedo said.

Anderson at Denver Health thinks a big part of the problem is education. Everyday cyclists tend to know more about road safety, such as wearing bright clothing at night, wearing a helmet and yielding to pedestrians. Since scooters are newer to city streets, she thinks people do not know enough about safety measures. She said she wants to see the scooter companies lower speeds and do more to prevent minors from riding. She also wants cities to better educate riders, fix their sidewalks and lower car speeds, especially on side streets.

But helmets remain an ongoing issue, as head injuries are some of the most serious outcomes from crashes. Denver Health budgets to give out helmets to bike and scooter crash victims with head injuries; Anderson estimates that she has given out more than 1,200 helmets so far this year.

"But then how do you put helmets on the scooters?" she asked. "I'm not going to put the helmet on that the person before me [wore]. So I think that that's a big issue. I do not have the fix on that one at all."

Caicedo, who ended up with a concussion, cracked his helmet in three places during his collision with scooters.

"If I hadn't had a helmet on I would probably be dead," he said.

About two months after the hit-and-run, Caicedo returned to the site of the crash.

By then he was out of a sling and his ribs had healed. His clavicle will take a year or two to completely grow back, but Caicedo had decided against surgery. By then, he had missed dozens of days of work for doctor's appointments and physical therapy and the bills had started piling up.

"I didn't realize how much it was going to impact me," Caicedo said about the first time he returned to the Cherry Creek Trail. "The level of emotion and anger that came up, every time I see a person on a scooter now, I get angry."

Months after the hit-and-run, Caicedo had made no progress on identifying the people who crashed into him. Caicedo said he wants two things from them: to cover his hospital bills, and to ask them why they fled the scene.

"They left me after they hit me, so I want to understand why they would injure somebody, whether it was their fault or not, that they didn't have the ethical or the morality to stop and help somebody that was injured," he said. "They just abandoned me when I got hit."

Caicedo recounted the crash and his recovery while standing on the ramp entering the Cherry Creek trail near Wewatta Street, where the scooter riders had ridden down moments before colliding with him.

While Caicedo talked, nearly a dozen electric scooter riders came down the ramp onto the trail over the course of twenty minutes. Some paused briefly at the yield sign and glanced to the right, making sure no one was coming north on the trail. But none of the riders looked to their left for people heading south, the direction Caicedo was riding before his crash. Some riders did not yield at all, speeding right on to the trail, only avoiding pedestrians or cyclists by pure luck.

Thanks for the support, Denverites!

Thanks for the support, Denverites!