Yubisay Fonseca is rushing to pack. So are her three children, her husband Carlos and the rest of her family — and more than a hundred neighbors.

They have until 7 a.m. on Tuesday — less than twelve hours — to leave their apartments before Aurora Police push families from the building where they live and block their return.

In recent weeks, there has been a string of crimes at the building, including shootings and an attempted murder.

For years, the building has fallen into disrepair. Trash has piled outside. Mold has grown from broken pipes. Animals have scurried through apartments.

And just a few days ago, the City of Aurora ordered the building’s closure in the name of safety — the end of this chapter for Fitzsimons Place, an apartment building near Colfax Avenue with 90-some apartments where mostly Spanish-speaking families live doubled up.

Anyone who tries to stay after 7 a.m. will be arrested. Anyone who leaves will be homeless until they figure out somewhere permanent to stay.

A mother sings.

Fonseca takes a break from packing on Monday evening. She stands on the third-story balcony of her apartment. With bags under her eyes and a hard-earned grin on her face, she belts a song in Spanish to her neighbors, exalting Jesus Christ.

Long live the faith.

Long live the hope.

Long live the love.

Long live Jesus Christ.

Long live the king.

To shut down the apartment building Fonseca calls home, the City of Aurora will leave dozens of kids, their parents and many others homeless, living in temporary shelter in hotel rooms through the end of August.

After that, the families are not guaranteed a long-term place to live, though the city has funds to offer for deposit money if people can find a place they can afford in a market with too little housing and unaffordable rent.

The city isn’t managing those renters’ cases. Nor is a big nonprofit like the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. A motley group of activists is in charge.

“We’re winging it,” said Nate Kassa, an organizer with the East Colfax Community Collective.

The City of Aurora says Fitzsimons Place is uninhabitable and that they’ve been fighting the property owner, CBZ Management, to clean it up for two years. Now the building’s even worse.

Fonseca says most of the people who lived there paid their bills, cared for their spaces, and did nothing wrong. Their landlord, who is in a court case with Aurora, abandoned them. The renters are the victims here.

And city officials agree.

Now Aurora is forcing the building’s renters to move and offering limited support, all distributed by what city brass say are valued community partners—community partners who say they need more help from Aurora city government.

The city surprised renters with just six days notice that they needed to move. Yet Aurora City Charter permitted 15. Earlier on Monday, residents went to the Aurora Municipal Building with the community partners and said they needed the full 15 days.

Why offer less than the allowed time?

Fitzsimons Place is too dangerous, city officials said.

That began a tangled process that would leave newly homeless families sitting on a sidewalk for 12 hours, with no bathrooms, no on-the-ground city worker support and no concrete plans.

The media received more frequent communication from the city than the renters, even as a handful of overworked volunteers did their best with what Aurora gave them.

On Monday night, Fonseca’s family packs what they can. The temperature’s dropping. The wind’s blowing hard.

Renters light up grills on all three floors of the complex. The air smells dangerous like the building caught fire, but it’s just grilled meat.

Fonseca shouts across the courtyard at her neighbors, waving. They wave back. She says she does this all the time.

“I know them, and I know them, and I know them,” she says pointing at doors on all levels, in every direction.

Most of her neighbors came from Venezuela. They have a community there at Fitzsimons Place, a safe haven in a foreign country with a language they don’t speak, food they don’t have a taste for and a culture they’re still learning to navigate.

She looks down from the balcony at laughing kids, including her 5-year-old son Gabriel, riding scooters and bikes, carving figure eights on stone paths below, oblivious that the police are coming in the morning.

“We’re moving,” is what Fonseca tells Gabriel when he asks why everyone’s packing up. There’s a lot she doesn’t tell him.

Below, older kids in the courtyard make bilingual protest signs begging the city for more time to pack. The city had already said “no” and wasn’t going to change now.

Fonseca’s neighbors carry sagging mattresses, overflowing boxes, washing machines and suitcases to rusted cars and trucks so old they are practically glued together.

“This is unjust,” she says.

The people living at Fitzsimons Place are not bad people, she says. They’re not guilty of the crimes the landlord has blamed on them — accusing them of being gang members. They’re a community of families with children — so many children.

A ragtag group of anarchists, socialists, students and neighborhood organizers help families scramble for shelter and housing.

Two volunteers from the East Colfax Community Collective and another from the Housekeys Action Network Denver sit on stones and folding chairs, collecting information from residents to help them find housing, with some success.

Anarchists pass out water bottles and snacks. They play with kids. They rage at a system they call racist, and wonder how it came to be that they’re the ones doing the government’s work.

Aurora calls these groups “community partners.” The partners need more help: flexibility with a move-out date, locked-down hotel rooms and support on the ground working with families.

The city offers none of that.

There is Angel, an aviation student with the East Side Community Collective, whose parents came from Mexico. He has been working all day without a break, translating the families’ concerns to other organizers.

There’s Emily, an English-speaking organizer. Her Spanish improves by the minute with every case she tries to solve. The kids dote on her. Parents drill her with questions, few she can answer.

There is V Reeves, a longtime organizer with Housekeys Action Network Denver, speaking fluent Spanish and recording families’ information as children shower the activist with hugs, dolls and candy. Reeves has been working all six days since the notice dropped to help the residents with their scramble. They plan to spend the night, in case SWAT teams raid the building early.

All three are trying to build the system as they implement it and will show up the next day and do it again.

Late that night, Reeves gathers in a circle with activists to tell them to divide into two groups in the morning — one to help with the move and the other to protest. They should avoid a conflict with police in front of the children. The kids have been traumatized enough. But away from children: Shame the cops and shame the city.

A mother robbed.

Eliza Pinto’s son and daughter had their first day at a school they won’t be returning to if they stay in a hotel too far away.

How was day one?

“Okay,” says the daughter, smiling like she doubts even that.

The son, sprawled on a bed bug-infested mattress, watches YouTube videos as Pinto’s husband moves out their belongings.

Pinto runs her fingers along the wall, pointing out where her family patched holes from previous tenants, painting over scars. The hot water quit working a month ago, so it’s been cold showers for all. There’s a big hole where the air conditioner once sat, with large slats letting in light and whatever else.

Her son’s stomach is covered in bites from bedbugs, she says, and so are her arms.

This is nothing new. She scrolls online through reviews of Fitzsimons Place from five years back. Old tenants described rats and bugs, probably the ancestors of the squatters that plague her family.

She’s baffled. She paid the deposit. She paid months in rent. How can she not have a home now? The landlord owes her family the money back, but she doubts she’ll get it.

“He has robbed us,” she says.

Instead of a refund, she’ll get police escorting her out.

“It’s horrible,” she says.

Before the cops arrive.

Throughout the night, organizers continue to enter families’ names and room numbers into a database. They stay up till 2 a.m.

The courtyard is quiet as the sun begins to rise again.

A few activists are helping families lug their belongings to the parking lot — a last-ditch effort to ensure everything important gets out before the cops arrive.

Still, the City of Aurora has no staff on site as people rush to meet the 7 a.m. deadline. A spokesperson for Aurora says city workers will be on their way soon. They’re still waking up and getting going.

Clusters of families, meanwhile, are gathering their belongings, babies and pets in the parking lot, waiting for city help.

Then come the police.

Just before 7 a.m., Aurora police officers walk into the parking lot and tell people to leave or they will be arrested.

Some renters are still moving.

“We need more time,” an activist tells officers.

“It’s not my plan,” one cop says. “I’m just doing my job.”

The activist wants to talk to someone in charge. The police officer tells him — and eventually all of the residents — to go to the corner of 16th Avenue and Oswego Street, where the officer says city officials will soon be available to answer questions.

Pinto is among the mothers who try to talk to the cops, who demand to be relocated to another apartment, who say they want more time.

Officers enter the courtyard of the apartment, climb the metal stairs and position themselves at the entrances on all three floors.

Others escort Fonseca and her neighbors from their home.

In the parking lot, families shout at officers. Police tell them to leave — there’s nothing for them here anymore. Their homes are no longer their homes.

Fonseca and Pinto join a group chanting in Spanish: “We want solutions.”

The police, mostly English speakers, stare confused, telling them to leave or they will be arrested. This is the only message these renters hear from the City of Aurora today.

As the crowd leaves, officers explain that the Sheriff's Department usually handles evictions, not police. This is not an eviction but an “abatement.”

Of the people we speak to, only one person sees an officer or city worker lend a hand — someone from animal control who helped a family get cat food.

The police shut down 16th Avenue and keep an eye on the crowd.

Other than officers standing behind police tape, there are no city officials who can answer renters’ questions at the corner of 16th Avenue and Oswego Street, as promised.

The displaced renters are not brought inside. They have no toilet to use and few places to find shade. Cars drive through, as kids play in the road. Not a cop, but an activist, directs traffic.

The same organizers who were typing names into databases last night are doing so still.

At first, Fonseca and Pinto join a crowd — a mix of renters, parents, children and activists — who yell at the police while they wait for a hotel room.

“We want solutions,” they reiterate in Spanish.

But the families are tired. Soon they sit, and the activists chant in English.

“What are they saying?” Pinto asks.

The protesters are comparing the cops to the Ku Klux Klan, a reference lost on Venezuelan immigrants. The activists dub the officers “colonizers” and accuse them of being “murderers.”

They bring up the killing of Kilyn Lewis, a 37-year-old man shot dead by Aurora Police in May.

Hours pass. People wait.

Three volunteers from the East Colfax Community Collective try to organize the relocation of more than 100 people. They take no breaks. They have few solutions. They’ve been going at it since Monday, and they’re worn down.

Still, they stay calm and focused and do what they can, even though the city has yet to secure enough hotel rooms. The day before, officials said there were 85 on hand. That wasn’t yet true.

Organizers say contracts between the city and hotels have not been signed, deals have not been struck, and then some fall apart. Those 85 units were an overpromise — at least for most of the day. Eventually, some units open up.

Mid-morning, an irate woman drives her car through the crowd, aiming it at renters and organizers. People chase her down, slamming their fists into her car.

Rumors spread that she kidnapped a child. Or did she hit a child with her car? Or did she almost hit a child?

The police rush toward her and question her. She does not appear to have a child and no kids appear to have been harmed. The families walk away.

And they wait some more.

“We have to be patient,” says Carlos, Fonseca’s husband.

Gabriel, her five-year-old son, is swinging a plastic sword around. He climbs a fence. He runs across the school’s sports field to a playground. Climbing back over the fence, he winces as a bee stings him. He melts down and falls asleep under a canopy.

Other kids juggle a soccer ball in a circle.

A mix of volunteers and residents gather around a car that’s blasting Mexican superstar Gloria Trevi. They wave a rainbow flag.

Nearby, a group of young men listen to hip-hop on their phones.

And they wait.

Volunteers deliver meals: burritos, rice and chicken, and cheese and meat sandwiches. They pass out countless bottles of water.

The sun blares down. Families keep asking for help, the organizers keep trying, but there’s little they can do.

TV crews come and go. People tell reporters about the injustice. Mostly, they try to stay cool.

A biker zooms up on a Harley and asks what’s happening. A volunteer explains.

“Are they illegals?” he shouts. “Call ICE.”

He roars off.

The afternoon drags on.

A few outside nonprofits look for rooms for renters, some more permanent and others in hotels. They manage to connect a few families to shelter — for a while.

Fonseca is confident that since she was placed in her apartment at Fitzsimons Place by ViVe Wellness, that the group will give her a room. At least, that’s what the organizers said.

She goes to the table for an update. Now, she learns, ViVe has no more rooms.

“Nothing,” she says, walking away.

“We need more space,” Angel says.

Fonseca and Pinto are still told there’s nothing for them yet.

“I’ll sleep in my tent on the street,” Fonseca says.

The cops still stand, arms crossed, waiting for orders to leave and watching roughly a hundred people wait for a place to go.

Slowly, hotel rooms open. Some are available soon, others not till 3 p.m..

The cops eventually leave. The apartment building is surrounded by fencing. Trash that piled for months is gone. The last trace that the City of Aurora was involved on the ground fades.

More families pack up. Some take buses, before tickets provided by the city run out. Activists drive others.

When most families learn they have a room till the end of the month, they cheer. Then they look around nervously, sad their neighbors are still stuck on the sidewalk. They hug their friends and say goodbye.

Eventually, Pinto’s family learns they have a place. They make their rounds and drive off in an SUV. She’ll worry about where her kids go to school later.

Family after family goes. Then the flow stops.

“Nothing at the Comfort Inn,” says Emily, who has been working nonstop. “Nothing at the Quality Inn.”

Here and there, she can find a room for families. But not many.

“I’m trying to get the city to get us more motel rooms,” Emily says.

Aurora officials say they’re looking. Finally, 10 more come through. And more families leave.

Fonseca, meanwhile, has one of the largest families. They need two rooms. She’s among the last to still not have a place to sleep.

So she says goodbye to friend after friend and waits at the table with hope. Every time Emily says not yet, Fonseca shakes her head. Seven people in her family could be on the streets.

She sits on the curb, head hung low, drawing a heart with chalk.

Around 5 p.m., her name is called. Her family has two rooms secured at a Quality Inn, many miles away.

She, her sons and her husband say their goodbyes. They hug their friends and rush to their beat-up SUV.

On the drive, she cradles Gabriel in her arms in the back seat.

Fonseca and her husband Carlos don’t know how they will cook food without a kitchen. They don’t know how they will get their kids to school. They are starting from scratch again.

But still.

“I’m relieved,” Fonseca says.

Her 24-year-old son looks at a lottery ticket and tells his dad, Carlos, how close he was to being a winner: Just one number was missing in the mix.

They walk inside the Quality Inn. There’s a long line, with many people coming from the shuttered apartment.

The woman at the front desk is flustered. She doesn’t speak Spanish. She’s recruited one of the bilingual housekeepers to help her speak to the guests.

After navigating some confusion, finally, Fonseca and her oldest son each get a key to their rooms.

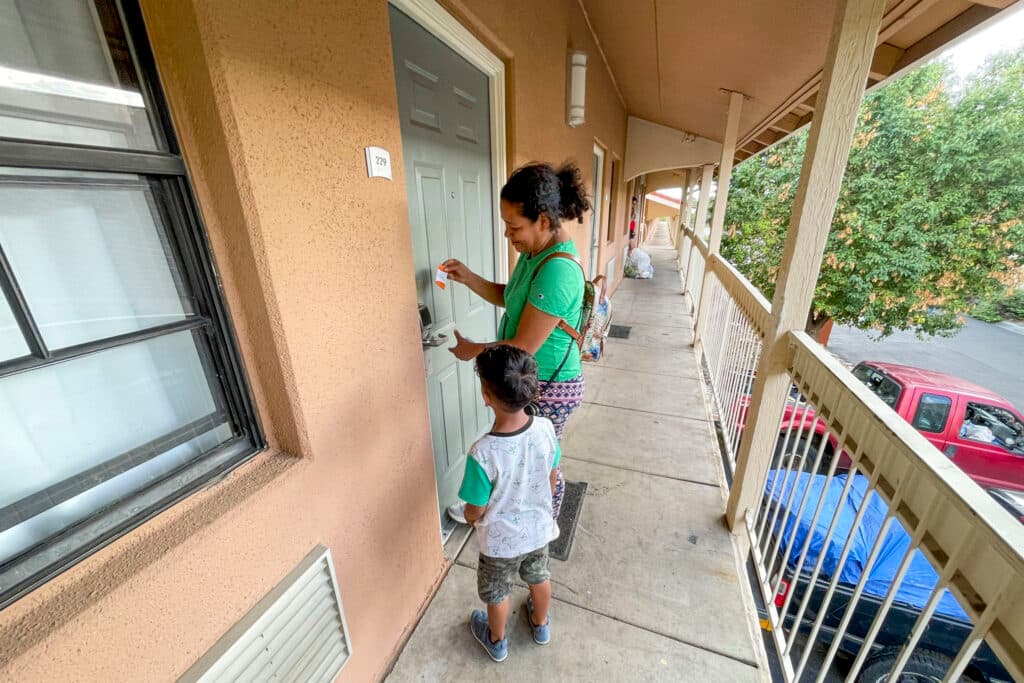

Fonseca and Gabriel walk around the building, hand in hand. They climb the stairs. Gabriel counts down the numbers on the doors until they get to their room.

The door is stuck. It takes a few minutes to jiggle it open. When they walk inside, cold air blasts them. Gabriel jumps on clean sheets and starts dancing and dabbing. Fonseca flashes a peace sign.

And they look around the room. They have a big TV, neatly made beds and a little soap bar in the bathroom.

Best of all, they have a kitchen with a hotplate, a coffee pot and free coffee, a microwave and a medium-sized refrigerator. They will be able to cook at home.

Back at the family’s old SUV, Carlos realizes the keys are locked inside.

He tries to pry open the door. He attempts to use his knife to jimmy the lock. He begins to crack through the rear window with the butt end of his knife.

Before he breaks the glass, an old scraggly man standing on the hotel balcony shouts down: “Did you lock your keys in the car?”

Carlos doesn’t understand at first, but eventually, he gets the jist, stops pounding the window, and nods.

The old man — shirtless, sunburned, tattooed — comes down, swiping his long white hair from his eyes. He sorts through his tools and finds a kit to open a locked car.

“I don’t know if this will work, but I’ll try,” he says.

The two men, communicating through gestures, manage to pull back the door enough to slide an airbag inside. They pump it up and use a long metal rod to slide open the lock.

“Thank you,” Carlos says in English.

“Alright,” the man says, noticing Carlos’ backpack is sitting in front of the SUV. “Don’t forget your bag.”

Carlos laughs. He needs that bag. His family left almost everything behind.