Denver’s fast-moving, multi-lane Speer Boulevard is not the city’s most pedestrian-friendly street.

But what if it was?

The road, parts of which are among the city’s most dangerous corridors, could be radically changed if the city follows through on a new study that recommends an overhaul of Speer Boulevard between Colfax Avenue and Interstate 25 as it moves along the Auraria Campus, River Mile and Ball Arena area and much of Lower Downtown.

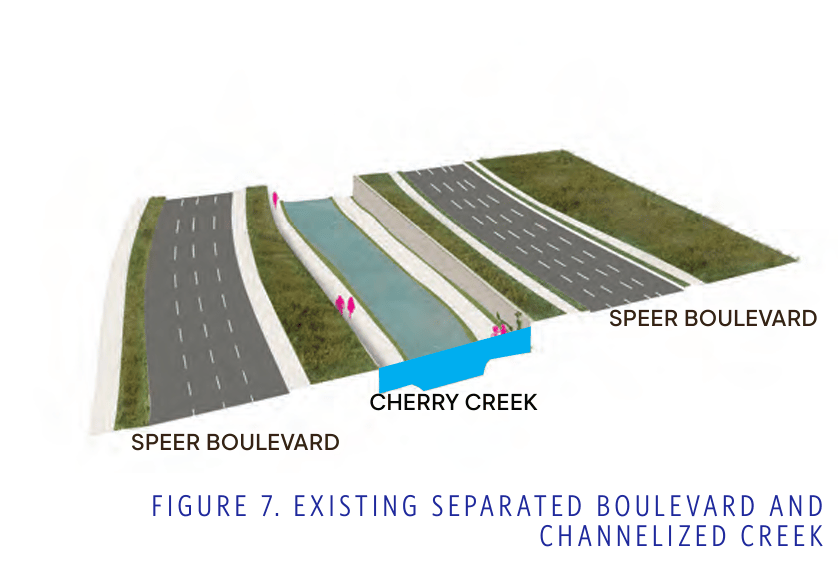

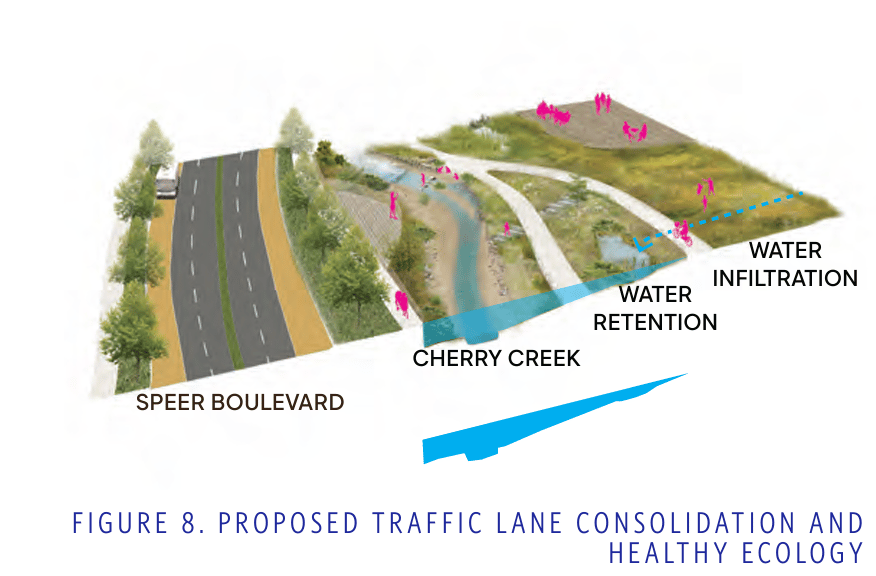

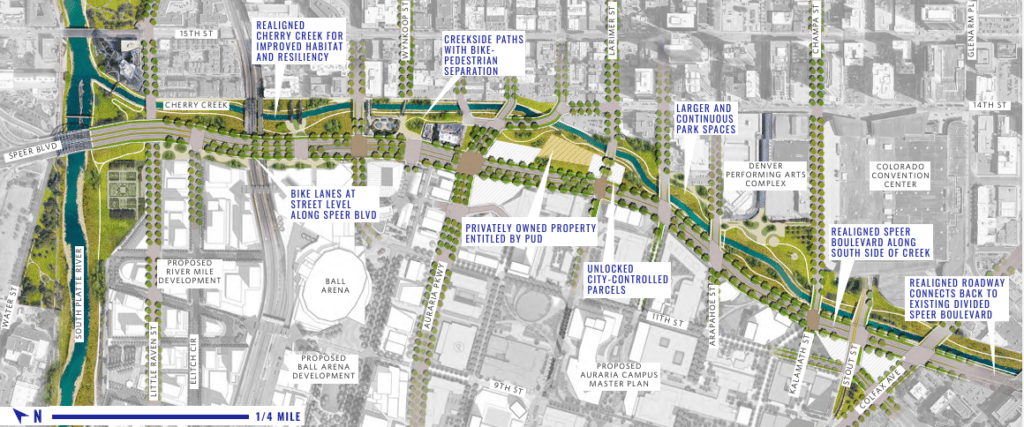

The study’s authors — a group of architecture firms commissioned by the city — suggest reformatting 1.5 miles of Speer Boulevard. Right now, the boulevard includes a pair of busy one-way streets, one on each side of Cherry Creek. This new “vision” would reduce it to a single road, with two lanes in each direction, occupying just a single side of the creek.

This change would be a massive overhaul to one of the busiest streets running through the heart of downtown. With Speer relocated to only one side of the creek, the entire other side could be freed up and turned into a landscaped series of public parks and recreational space.

The study also imagines the eventual addition of bus rapid transit — known as BRT — along Speer Boulevard, which could include a series of dedicated bus lanes and upgraded bus stops for faster public transit along the corridor.

(Elsewhere, the city will break ground on Denver’s first BRT line, which will run along East Colfax Avenue, this fall.)

The new Speer vision could turn what is essentially a highway through the heart of downtown into a pedestrian and transit paradise.

Making the change, however, would require hundreds of millions of dollars, years of planning and a significant change to how people navigate the corridor. Right now, it’s just a 54-page report and a grand vision. And there’s a long history of grand visions for Speer. Here’s what it might take to make this one happen.

The study imagines a future Denver with better public transit and fewer cars.

The new vision for Speer Boulevard comes as the city is reimagining much of downtown. Developers plan to transform 55 acres of parking lots around Ball Arena into housing, hotels, office space and entertainment venues.

That means the area around Speer Boulevard could see a massive transformation in the next few years.

“Historically, Speer has been used by drivers and vehicles moving in and out of the city, often bypassing downtown,” the study’s authors wrote, adding that planned redevelopments would “reposition Speer from an arterial at the city’s edge to a street within the city’s center.”

Jill Locantore, executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership, has advocated for pedestrian upgrades to busy city streets for years. She wants Speer to be a part of the downtown transformation in the coming years.

“It's designed like a highway when what it needs to be is a people-friendly Main Street,” she said.

Speer used to be more pedestrian-friendly.

Robert Speer, who was in office from 1904 to 1912, and again from 1916 to 1918, was a big proponent of the nationwide “City Beautiful” movement that sought to create, well, beautiful places to promote “social harmony and increased civic virtue” in what were otherwise drab, dirty industrial cities.

In Denver, Speer pushed for the creation of new parks and parkways. One of his most consequential road projects was the redesign of what was then Cherry Creek Drive, which at the time was lined with shanties and industrial ruins, into what is now Speer Boulevard.

Famed city planner and landscape architect George Kessler and Denver’s own landscape architect S.R. DeBoer upgraded much of the road to a tree-lined drive with new parks, lampposts, and other amenities that enhanced the pedestrian experience, according to The Cultural Landscape Foundation. The creek was walled to keep it from flooding.

It was “the heart’s desire of the mayor that his name shall be perpetuated,” the Rocky Mountain News reported in 1908, so the city’s board of supervisors “railroaded through” a resolution renaming the road to Speer Boulevard in his honor.

In the 1950s, as Denver fully embraced the automobile, city traffic engineers converted Speer Boulevard and what was formerly known as Forest Drive into two one-way thoroughfares designed to pump traffic along the creek as quickly as possible.

“This would also be a good street to try enforcing [minimum speed limits],” one approving Rocky columnist wrote in 1958. “After all, one slow poke can hold up a whole line of cars.”

Apart from the Cherry Creek bike and walking path, which was designed in the 1970s and built years later, Speer has remained dominated by speeding cars ever since, though drivers all too often end up crashing into the creek itself or the path next to it.

Some dreamers, however, had big ideas for how to dramatically reshape Speer over the years.

One out-there idea from the late 1960s would have added transit without infringing on car space. Noted railroad artist Otto Kuhler proposed an elevated monorail loop around Denver that would’ve straddled the creek.

That, of course, was never built.

Denver is about to re-pedestrianize and cut car space on other key roadways.

With the Colfax Avenue Bus Rapid Transit project breaking ground in October, the city is going all in on bus transit along that corridor. The nearly $300 million project, funded with a mix of federal and local money, will drop the infamous car-centric street down to just one lane in each direction between downtown and Aurora.

Plus, earlier this year, City Council rezoned large parts of that stretch to promote pedestrian-facing businesses over drive-thrus in anticipation of the BRT. Denver and state transportation officials are also studying a potential BRT along Federal Boulevard, one of the city’s most deadly streets.

In June, city officials also broke ground on a $15.5 million pedestrian improvement project along West Colfax that will add medians, signal crosswalks and landscaping along portions of the road.

Denver City Council is also thinking about how to better use Denver’s downtown waterways. A new Council committee started in July is thinking about how to make the South Platte River, which intersects with Cherry Creek and Speer, more accessible and better integrated into the city.

Reshaping Speer could be easier said than done.

The Speer plan acknowledges that a traditional traffic study might conclude that eliminating half of Speer’s traffic lanes wouldn’t be feasible because it could cause traffic gridlock.

But the study’s authors say a metamorphosis of the corridor is indeed possible — if 40 to 50 percent of the more than 5,000 drivers per hour that use Speer at peak times can be convinced to switch to transit, bicycle, or some other form of transportation.

Any bus service along this stretch would be starting from scratch, though. Unlike on Colfax, which holds the busiest RTD bus lines in its system, there is no local bus service along Speer north of Broadway. RTD cut its services significantly during the pandemic and has limited plans to restore them.

Still, Locantore, who helped advocate for projects like the West Colfax upgrades, has pushed for city and state leaders to extend their BRT plans to include this stretch of Speer. She believes a transformed Speer could happen.

“That's exactly the kind of change that we need, but we'll see how bold the city is willing to be in reimagining this particular corridor,” she said. “It would take community support, political will and funding.”

The study’s authors estimate their proposal would cost nearly $600 million to build — about double the cost of the Colfax bus project. That money isn’t in the budget just yet, and the city hasn’t announced its next steps.

What do you want the future of Speer Boulevard to look like? Drop us a line at [email protected].